With the fixation on the debt ceiling, perhaps the biggest disappointment arising from Washington over the last several months has been the lack of focus on jobs. This week's updated Labor Department study on private sector business employment offers a sobering reminder of the precarious nature of job creation among small firms after the nation emerged from the Great Recession.

The Labor Department's quarterly Business Employment Dynamics report catalogs the number of gross job gains from opening and expanding private sector establishments compared with the gross job losses from closing and contracting private establishments. The national economy exhaled to a degree with the Great Recession in the rearview mirror during the fourth quarter of 2010: i.e., the difference between gross gains and losses was a net accretion of 563,000 private sector jobs. By contrast, there was a net loss of 228,000 jobs at the recession's trough in the respective last quarter of 2009.

Yet, what is surprising about 2010 was the diminished contribution of private sector jobs by very small firms. Small firms dominate the business landscape and, when liberally defined by firms with less than 500 employees, they account for roughly one-half of the nation's total private sector payroll. We've all committed to memory that the small business sector is the country's supreme job growth engine. But the fact is that there's a lot of churn in the small-business labor market, and small businesses under 50 employees substantially lagged bigger business firms in net job generation in the year following the end of the Great Recession.

For instance, of the 1.02 million net private sector jobs added in all of 2010, large firms with 250 or more employees accounted for a whopping 617,000 jobs, or 60% of the total. On the other hand, small firms with 50 or less employees barely hired anyone, comprising only 3% of the total net job gains. Moreover, in the fourth quarter alone large firms of 250 employees or more produced 73% of all new jobs while small firms under 50 employees contributed only 9%. These results come about because while the smallest firms produced 54% of the gross job gains in 2010, they also were responsible for 53% of the gross job losses.

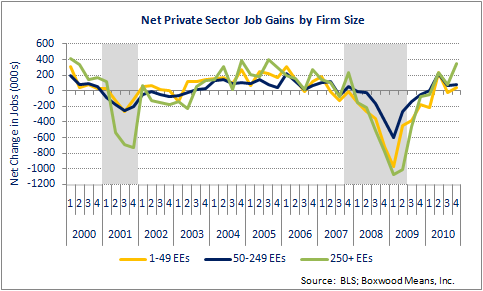

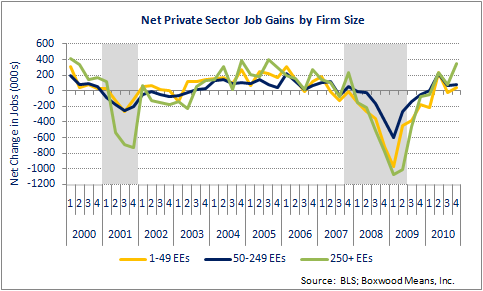

The nearby graph illustrates a couple of interesting job creation trends. First, the dominant role of larger firms with 250 employees ("EEs") or more during 2010 is self-evident. In particular, note that while both the largest and smallest firms suffered deep net job losses during the Great Recession (area shaded in grey), the former group added net job gains at a much faster and prolonged rate than the latter after the recession ended.

In addition, by contrasting job recovery after the decade's two recessions it is clear that the extended duration of the Great Recession - the longest since the Great Depression - imposed greater hardship on the smallest firms relative to larger-sized ones. During the 2001 recession, net job losses for the smallest firms were relatively shallow, and firms with 50 employees or less led larger-sized firms in net job creation during the ensuing and aptly named "jobless" recovery: e.g., the smallest firms gained 140,000 net jobs during 2002, while firms with 50-249 employees lost 178,000 and businesses with 249 or more workers lost 376,000. But the impact this last time was different: the severity of the Great Recession pinned down and delayed the resurgence of the small business sector to a greater degree than larger firms.

Before we wrest the No. 1 job creator mantle from the shoulders of the small-business sector, let's remember that lending to small businesses was extremely tight last year and was a major factor in the underwhelming contribution of small firms to economic and employment growth. (See SmallBalance.com's MarketBeat story, "Epitaph to the Credit Crunch: Small CRE Business Lending Tumbled" for additional insight on recent small-business lending.) Meanwhile, larger firms that typically possess better access to credit were capable of making additional business investments last year including a greater percentage of net new hires.

Clearly, small-business financing is a key ingredient that primes the pump of the nation's small business growth engine. The statistics in this report, albeit a little dated, underscore the peculiar weakness in the small-business economy that persists today. Now, nearly two years beyond the end of the Great Recession but with the nation's economy still floating in uncharted waters, strengthening small-business financing is likely one of the most productive things that Washington and industry at large might focus on.